First published by Dusty Weis, Association of Equipment Manufacturers

At the urging of local officials, contractors on the $524 million project have approached hiring challenges with bold, unconventional workforce development strategies that help people get needed job training. Equipment manufacturers that struggle to find skilled workers could replicate these successful workforce development program models by utilizing new recruiting software that links applicants to needed training, partnering with local governments, connecting with the community and utilizing regional job training services.

From a distance, it looks like any other large-scale work site. Newly-placed steel girders arch overhead as hundreds of yellow-vested workers swarm over the NBA’s newest arena in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, still a year away from its completion in time for the 2018 basketball season.

But a closer look at the construction crews reveals a workforce made up of at least 40 percent Milwaukee residents who were, until recently, underemployed, jobless or even unskilled. These nontraditional work crews are gaining valuable on-the-job experience and providing for their families thanks to a partnership between the Bucks and the city of Milwaukee aimed at helping disadvantaged urban residents benefit from the city’s boom in downtown development.

In order to meet the city’s hiring requirements and qualify for public financing, Bucks Senior Vice President Alex Lasry says the organization and its contractors have had to implement a creative workforce development strategy template, employing unconventional recruitment efforts and even finding ways to train underqualified workers. But he says the benefits of putting local people to work on the project go beyond good corporate citizenship, and he sees lessons that other employers, including equipment manufacturers, could apply to their own hiring efforts in urban areas.

“There are qualified workers out there, and there are people who want to work that are out there,” Lasry says. “I think what separates us really was the outreach and the dedication we’ve had to making sure this was a top priority of the project.”

Workforce Development Program Models that Break the Cycle

This untapped labor pool starts just a dozen blocks to the north of the new arena, where people are buzzing over a different development. In the city’s Bronzeville neighborhood, a small supermarket has opened in what was once a boarded-up pharmacy, providing residents with convenient access to fresh fruits and vegetables for the first time in years.

In its subtlety, the transformation taking place in this historically African-American neighborhood contrasts with the $524 million arena and massive high-rises going up in downtown Milwaukee. But, in a zip code where the median household income hovers around $30,000 and unemployment is over 15 percent, the slower, more gradual improvements are no less important.

For decades, this and other Milwaukee neighborhoods have been mired in a cycle of poverty, where finding a job requires skills and experience, but skills and experience come from holding down a job.

“That cycle, sometimes it’s not just the economics,” says Alderwoman Milele Coggs, Bronzeville’s representative on Milwaukee’s city council. “It’s mental, too, it’s emotional. Once you’ve been caught in that cycle, you start asking, how many more jobs am I going to apply for and get denied?”

So when negotiations began over the incentives the city would offer the Bucks to build their new arena in Milwaukee, Coggs and her colleagues in city government saw an opportunity to help break that cycle. In exchange for city financing assistance, the Bucks would have to employ at least 40 percent of their construction workforce from the city’s Residents Preference Program (RPP), which maintains a list of unemployed and underemployed city residents.

“If we’re putting taxpayer dollars into a project, it just makes sense that the taxpayers should benefit from that project,” Alderwoman Coggs says.

On a project that will employ thousands of people across several years, Lasry says meeting the city’s 40 percent RPP requirement while staying on-time and on-budget is no simple task. “There are only so many qualified, experienced workers,” he says. “But just because it’s difficult doesn’t mean it’s impossible.”

To address the challenge, the team pledged $375,000 to workforce development and training efforts, and asked the city to make a matching pledge, launching a one-of-a-kind partnership.

“We weren’t going to BS around and hire people to just sweep floors or hold up a sign,” to meet the RPP goals, Lasry says.

Build-Your-Own Workforce

As the Bucks arena project was ramping up, another major addition to the Milwaukee skyline was winding down. At a price tag of $450 million, the new high-rise headquarters for the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company employed more than 40 percent of its construction workers through the RPP—many of whom then joined the ranks of the Bucks arena workforce.

“I think that’s great,” Alderwoman Coggs says. “The point is not just to have people temporarily hired, but to give them the skills to get hired on an ongoing basis. Northwestern Mutual went above and beyond to ensure that they would meet and exceed those numbers.”

But other developments were tapping into Milwaukee’s RPP well of workers too, and, in order to meet their quota, Lasry says the Bucks had to build their own workforce through training and recruitment. Their first innovation was to employ a new piece of online software called SkillSmart Seeker, which helps create a path to employment for unqualified workers who would typically receive an outright rejection.

Lasry says all job applicants can apply via SkillSmart Seeker, which charts their qualifications and certifications. In cases where applicants come up short, SkillSmart Seeker creates a list of steps they can take to qualify for a job and connects them with resources to complete those steps, including local jobs training agencies, technical colleges and apprenticeships.

“We’re not telling anyone no,” Lasry says, “we’re just telling them not yet.”

“So many people may not have the proper certification, but they’re willing to get it,” Alderwoman Coggs says. “If they know what they need to do, they could go get qualified for future opportunities.”

And there will be many such opportunities. In addition to the arena, the basketball team is building or plans to build a practice facility, a sports clinic, an entertainment block, apartment buildings, parking garages and more. With 10 years’ worth of ancillary development in the works, Lasry says it will be to the team’s advantage to grow the pool of qualified workers.

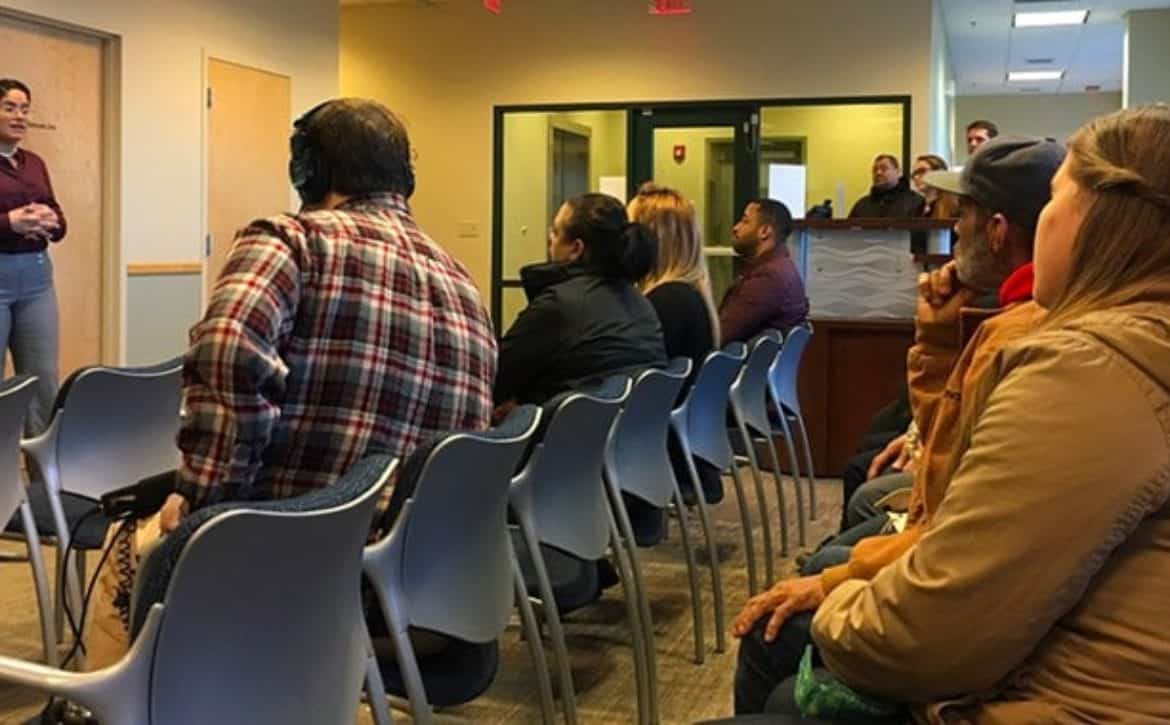

So, with SkillSmart Seeker as a conduit for training new workers, Lasry and his team set about getting more people into that pipeline. Instead of a traditional job fair at the team’s headquarters, they offered opportunities directly to people in their own neighborhoods, holding “jobs town hall meetings” in nearly a dozen different parts of the city. Hundreds of Milwaukeeans turned out, many from disadvantaged backgrounds, and each was given an opportunity to sign up for SkillSmart Seeker and register for RPP on-site.

Read full article

Learn More First published by Walmart, March 22, 2018.

First published by Walmart, March 22, 2018.

Veterans and their spouses have the right skills.

Veterans and their spouses have the right skills.